Gasoline Retailers Find the Big Inning with Price Margins

Baseball teams like the New York Yankees are often criticized because they depend on the “Big Inning” to juice up the win column. Similarly, the retail gasoline business is moving through its own “Big Inning” that rivals anything witnessed in the last 13 months.

Over time, gasoline price margins tend to be unremarkable. Investors accustomed to quarterly reports that tout 20% to 40% gross margins for technology firms don’t get excited by the very limited returns on fuel.

OPIS has been measuring fuel industry wholesale and retail averages since 1997 and there has never been a year where the average gross margin topped 10%. The highest year on record was 2016, when the amount separating the eventual street price and the cost to operators was 9.4%.

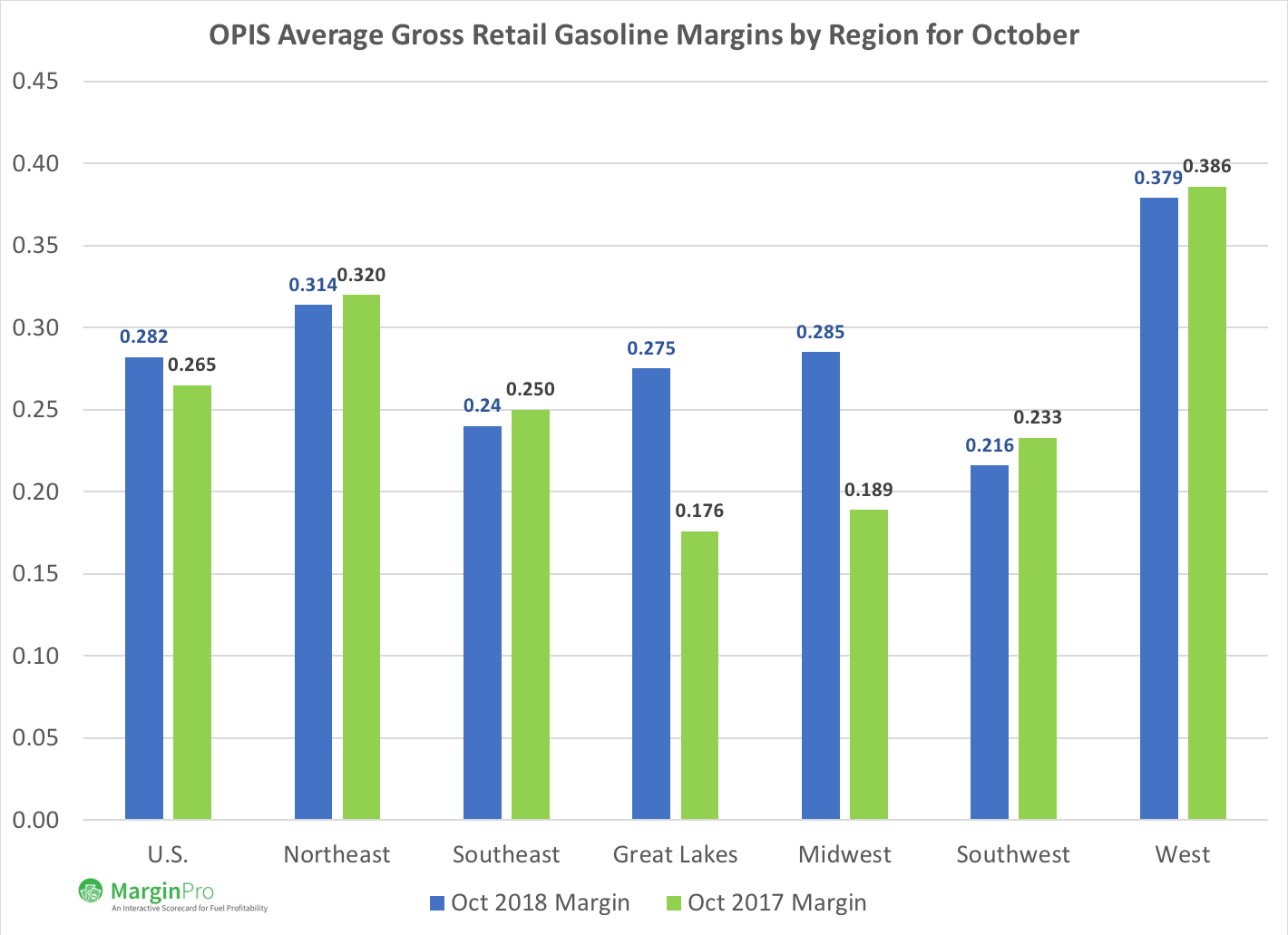

Beyond being unremarkable, profits on fuel can be incredibly uneven and 2018 has been a particularly bipolar year. October was a manic month, with gross price margins topping 28.2cts/gal across the 130,000 or so stations tracked by OPIS. The country was led by the West, where it’s not particularly unusual for gross margins to sometimes approach 40cts/gal. But profits for selling fuel soared in all portions of the country and the first few days of November find an eye-popping 50,234 sites – or 38.6% of the stations in the United States – selling regular gasoline for more than 40cts/gal above cost.

The strong autumn performance underscores one of the great myths of the U.S. gasoline business. Consumers tend to believe that gasoline retailers prosper when street prices rise, and conversely empathize with station operators as prices decline.

But the inverse is generally true. Wholesale gasoline prices have declined by 35-60cts/gal in the last month and street prices have dropped by less than a dime in most areas.

Why don’t prices drop with the same speed as they rise? There’s a simple answer. When prices rise, the station operator has the choice of losing money on fuel sales or ratcheting prices higher to capture some margin. When wholesale prices decline, there is no urgency to lower prices since the cost move is almost always independent of changes in consumer behavior. Hence, prices tend to rocket higher, but dip with the urgency of a dry feather falling to earth on a balmy day.

While all gasoline retailers have had a banner autumn, some regions perform much better than others. The best October (and beginning of November) occurred not in a single state but instead in the District of Columbia. Some 111 outlets monitored by OPIS there show that retail gasoline fetched an average price some 58.8cts/gal above costs at the bulk terminal. The top state was California, which, despite various carbon-related additional fees, saw regular gas fetch 45.3cts/gal over cost.

At the other end of the spectrum, Delaware may be known as “The First State” but it regularly ranks close to last in terms of gasoline profitability. Delaware operators were still able to sell gasoline for about 12.5cts/gal in gross margin, but the make-up of the state underscores the differences between the c-store sales model. New Era retailer Wawa has a dominant position in the state, and makes far more profit on robust inside sales. Gasoline is simply an enticement to drive traffic for its best-in-class grocery and food service business.

But between both extremes, there was a renaissance in fuel margins, which when measured in dollars spent still represents the number-one category for c-stores. The full year of 2017 saw average gross margins on regular gasoline of 21.8cts/gal. In October 2018, 43 states and the District of Columbia easily topped that mark, with November commencing with even more room thanks to a still-descending oil market.

Looking over the 437 MSA’s (Metropolitan Statistical Areas) followed by OPIS, one can grasp the impact that a big inning can have on the retail gasoline game. Smack dab in the middle of the MSA profitability rankings lies the East St. Louis MSA with 294 stations. Last October, retailers sold 87-octane regular at an average price of $2.377/gal, compared to a cost of $2.253/gal, for a gross margin of 12.4cts/gal.

There is incredible diversity in volumes depending on the station footprint, but OPIS calculates that an average U.S. station moves about 92,000 gallons of gasoline per month. On that basis, the gross profit margin for the hypothetical station in October 2017 would have been $11,408. Credit card fees, labor, lighting, rent and other expenses might easily add up to $10,000 per month per station, keeping a tight lid on actual net profit.

Now, consider the same station in October 2018. The average retail price was $2.781/gal, while the cost was $2.517/gal for a gross profit margin of 26.4cts/gal. The arithmetic suggests a gross profit of about $24,288 before overhead. Credit card fees, which are indexed to sales prices, cut into the margin, but it’s easy to see how the month delivered about twice the returns that were seen a year ago.

Beneficiaries of Those Big Innings for Gasoline Price Margins

The beneficiaries of the big inning are often the large private and public chains that own the real estate and company-operate the stores. Individual dealers, who account for ownership of about 50% of all the gasoline stations across the U.S., saw upside, but nowhere near the extent of the operators with scale.

In the publicly traded space, there are clear winners.

Couche-Tard, the Laval, Quebec, chain that operates 6,451 stores in the U.S., saw a surprisingly modest increase with average margins of 18.2cts/gal, up 6.6% from last year. Likewise, Murphy USA saw its October margin edge modestly higher to 16.4cts/gal, about 3.2cts/gal better than October 2017. Casey’s, which has a critical mass of more than 2,000 Midwestern stores, clocked in with an October average margin of 26.6cts/gal, well above its target numbers.

But all three retailers saw explosive margin gains ahead of the first November weekend. Couche-Tard margins topped 26cts/gal; Murphy advanced to 22.8cts/gal; and Casey’s saw stores recoup about 32cts/gal above cost. Some late-inning thunder occurred for nearly all companies in the OPIS survey.

Truckstop chains did well. Pilot Flying J, which now includes a rising equity investment from Berkshire Hathaway, saw gasoline sell at least 20.9cts/gal above cost. Publicly traded TravelCenters of America was tops among the public companies last month with an estimated 26.4cts/gal separating its cost and the street price.

While the margins posted for Costco (11.8cts/gal) and BJ’s (17.3cts/gal) are far below regional and national competitors, fuel sales for these Big Box operators are magical. Both companies tend to purchase gasoline at prices several cents below smaller competitors, and making money on gasoline is viewed as ancillary to the main goal of increasing visits to warehouses.

There are many Costco fueling sites, for example, that move 700,000 gallons or more of gasoline per month. The company acknowledged in a recent earnings conference call that it saw a bump in 2018 volumes as well as a little bit more margin. The call occurred well before retail margins widened, but a 700,000 gal/month site selling at the October average equates to an October gross margin of an eye-popping $82.600 over the 31 days.

Big inning for the Big Box chain, indeed.

You can make the same comparisons Tom made in this blog in your own market, so you can become more profitable selling fuel.

OPIS MarginPro lets you grade your retail station’s profit performance against key competitors.